They wanted to put their mark on them. Represent their crews and where they come from.

That's why they climbed multiple floors of an abandoned high rise building in downtown Los Angeles – now dubbed “LA’s Graffiti Towers.”

Some say it’s a crime, a violation of city law, but those in the graffiti scene have spoken exclusively to NBC4’s I-Team and call it art.

Get top local stories in Southern California delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC LA's News Headlines newsletter.

“It was like a movie. It was pretty crazy,” one man, who did not want to be identified, said about graffiti at the towers.

If you pay attention, graffiti is very much a part of Los Angeles.

Without taking any position or condoning illegal activity, the I-Team wanted to find out more about the people who do it.

“I just felt like it was part of LA. It was like something like a memory. And then if you weren't there, it's like you're going to regret it later,” the member of the graffiti group added.

But some have argued the regrettable part is the graffiti itself.

“It’s really unfortunate that this once promising project has been so badly neglected that it’s become a national spectacle,” said Nick Griffin from the DTLA Alliance, a coalition of more than 2,000 property owners in the Downtown Center.

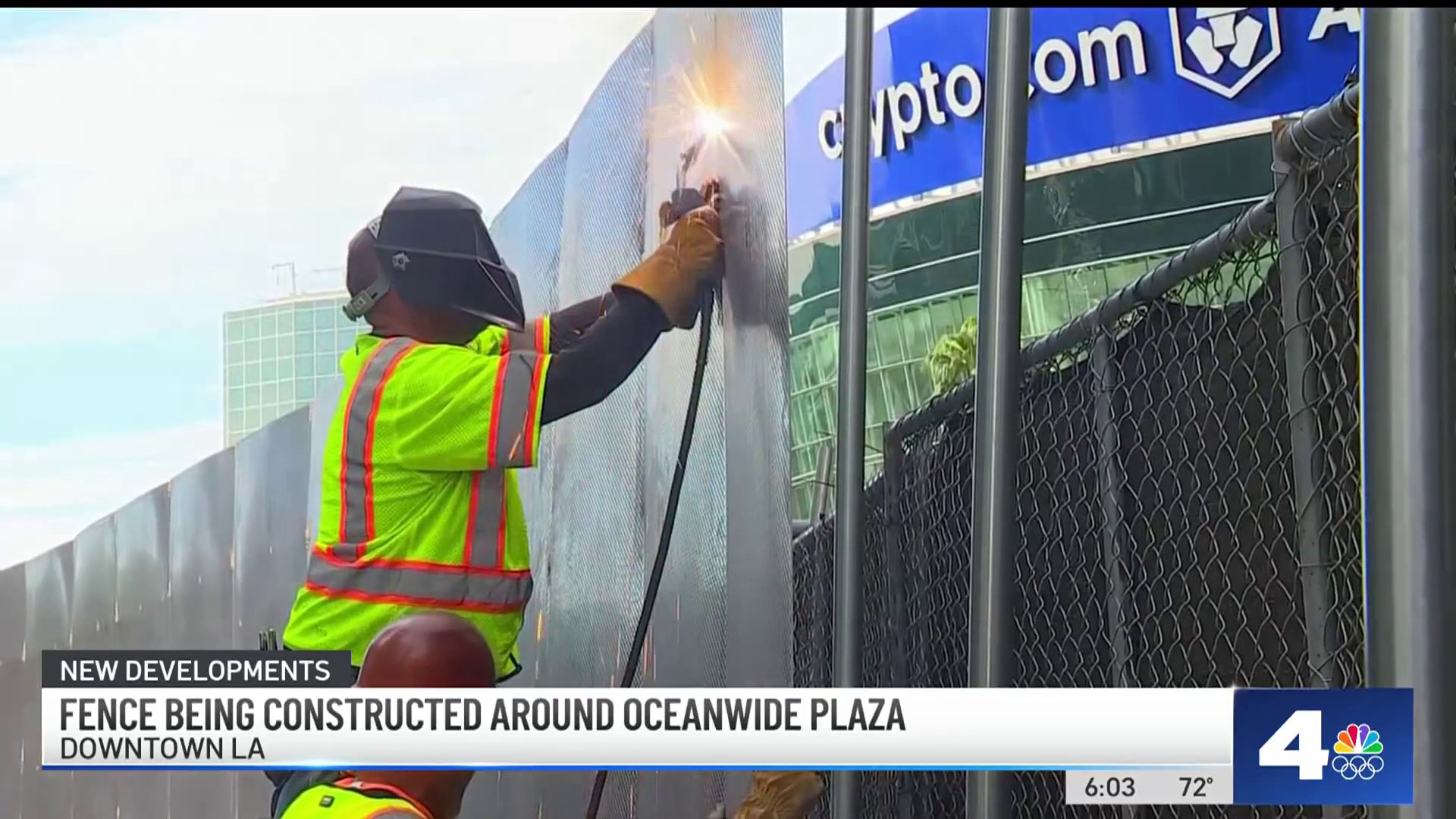

The city has turned its attention to the abandoned condominium and shopping mall project recently, years after the developers ran out of money in 2019, and some say only after the buildings became known as “LA’s Graffiti Towers.”

The city has now spent hundreds of thousands in taxpayer dollars to secure the area around the towers, and dozens of people have been arrested trying to climb over the fence around the plaza.

City Councilman Kevin DeLeon says the city will bill the developers for security and other costs.

"And then the worst part of it all is that the city of Los Angeles has now taken responsibility for it, and they're funding so much money to protect the buildings and paint them and all that where that money could be used anywhere else,” said Antonio Duran, who runs LA UNPLGD, part graffiti art supply store, part gallery space in the Florence Firestone neighborhood.

Duran, who says he is no longer doing graffiti, says he now showcases different people’s work and hosts monthly events at his shop.

“I became more self-aware that I could do more with the situation,” added Duran, who sells paint cans for $5 each and other merchandise, hoping people who think negatively of graffiti will see it differently.

"At the end of the day, it was still an illegal act -- what happened at those towers," Duran said. "I can't really condone nothing illegal. I try to promote more positive stuff, but it's definitely a way that the LA subculture has voiced themselves."

A few folks who say they are still part of the LA’s graffiti scene and participated in the towers took us to other parts of town, including one wall that they say has been painted for six years.

One man explains one particular piece of graffiti pays tribute to a friend who died.

“Just call it artwork. And then, like, memories,” he said when asked what he calls what he paints.

And when asked about going on people’s property, he says it's still "art."

"Anybody could take it how they want to take it. But as long as we know we're doing something good and it's not like we're throwing some gang letters or -- I get it," he said. "They look at graffiti bad, but we look at it as art. Like expressing what you have in your mind, your feelings. And we're expressing through paint."

In a 2009 ordinance, the city of Los Angeles calls graffiti “a blighting element,” “obnoxious" and “a public nuisance” that often lead to the “depreciation” of property values, “violence” and “genuine threats of life.”

"It is unlawful for any person to write, paint, spray, chalk, etch, or otherwise apply graffiti on public or privately owned buildings, signs, walls, permanent or temporary structures, places, or other surfaces located on public or privately owned property within the city," the city ordinance notes.

The people the I-Team talked to admit to crossing onto private property to "graph.”

What if the city set aside specific locations where they could showcase their work legally?

"I think there [are] places you could do that, but it'll ruin the whole, 'Take away the whole fun and the adrenaline,'” the man said.

For Duran, he says he created his space to show what graffiti means to him and so many others.

"We don't really promote vandalism or anything like that," Duran says. "We promote more self-expression and artistic ventures and stuff. Try to provide people with a separate medium for them to use."

The man who continues to graffiti says his and his crews do not mean to cause harm.

“There's other people that mess it up for the people that are really going out there doing art. But the majority of us is just trying to do something good and put something nice out there," he said.

Something nice or something unsightly seems to be left to interpretation even if the law is clear.