What to Know

- California appears in the midst of another drought just a few years after a five-year dry spell.

- The entire West is gripped in what scientists consider a "megadrought" that started in 1999 and has been interrupted by only occasional years with above-average precipitation.

- In California, the heaviest rain and snow comes in the winter months, but not this year. About 90% of the state already is experiencing drought conditions.

California's hopes for a wet "March miracle" did not materialize and a dousing of April showers may as well be a mirage at this point.

The state appears in the midst of another drought only a few years after a punishing 5-year dry spell dried up rural wells, killed endangered salmon, idled farm fields and helped fuel the most deadly and destructive wildfires in modern state history.

Get top local stories in Southern California delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC LA's News Headlines newsletter.

"We're looking at the second dry year in a row. In California that pretty much means we have a drought," said Jay Lund, a civil and environmental engineering professor at the University of California, Davis.

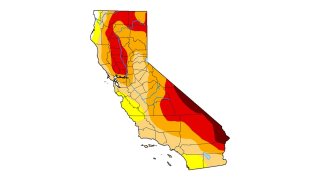

In fact, the entire West is gripped in what scientists consider a "megadrought" that started in 1999 and has been interrupted by only occasional years with above-average precipitation. In California, the heaviest rain and snow comes in the winter months, but not this year -- about 90% of the state already is experiencing drought conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

The weekly drought monitor's next report is due out Thursday.

Much of California's water comes from mountain snow in the Sierra Nevada that melts during the spring and summer and feeds rivers and streams that in turn fill reservoirs. The Sierra snowpack traditionally holds its peak water content on April 1 and the state will take a survey Thursday to determine the level. Last month, a survey showed just 60% of the average.

Four years ago, when then-Gov. Jerry Brown officially declared an end to a statewide drought emergency, he said conservation should continue, warning "the next drought could be around the corner."

California Snowpack Through the Years

It's arrival will mean different things depending on where people live.

The 2012-2016 drought required some sacrifice from everyone as Brown ordered a 25% reduction in water use. Residents took shorter showers, flushed less frequently and let their cars get dirty. Many homeowners replaced their lawns with artificial grass or desert succulents.

Such restrictions are less likely this time around because municipal supplies are in better shape and water use has not returned to previous levels, said Caitrin Chappelle of the Public Policy Institute of California. The Metropolitan Water District, which sells water to public agencies serving about half the state's 40 million residents, has a record high water supply.

But efforts to restore depleted groundwater aquifers or keep river flows high and water temperatures low enough for the winter-run Chinook salmon that almost went extinct on the Sacramento River during the drought, are not as far along.

"The time in between the end of the last drought and, possibly, the beginning of this next one isn't that long," Chappelle said. "They have started doing a better job of planning for it, it's just whether or not they've had enough time to prepare before the emergency hits again."

The Sierra snowpack provides about 30% of California's water and the Department of Water Resources measurement is key to forecasting how much can be allocated to farms and municipalities under a complex system of water rights laws that spell out what each user is entitled. The department already warned 40,000 water rights holders they will probably only get 5% of the amount they requested.

How Water Gets From the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the Rest of California

"Guys are in a really tough spot when they don't know what water's going to be available until the planting season, which is now," said Danny Merkley of the California Farm Bureau Federation.

With less water to draw from rivers and the state's intricate network of canals and aqueducts, farmers fallowed hundreds of thousands of additional acres.

Growers will likely do the same thing again, idling low-value row crops such as tomatoes, lettuce or onions, to commit their precious groundwater to high-value permanent crops like almonds, pistachios and wine grapes, Merkley said.

Tapping those wells could have ramifications for their neighbors. During the last drought, agribusiness was blamed for over-pumping groundwater, causing the land to sink and wells in some poor rural communities to go dry.

Lawmakers for the first time decided to regulate groundwater and require plans in the next two decades to stop over-pumping from aquifers. But groundwater levels have not fully recovered from the last drought with another looming.

In Tombstone Territory, an unincorporated area surrounded by orchards outside Fresno, three-quarters of the 50 homes lost their well water during the last drought, said Amanda Monaco of the Leadership Counsel For Justice & Accountability. Many residents are farmworkers who can't afford the $20,000 required to dig a deeper well.

"If we're headed back into a drought that means potential devastation for communities that we work with," Monaco said. "They're terrified that kind of thing could happen again."

Ray Cano was one of the first Tombstone residents to lose his well water in 2015.

"It started spitting air and then nothing came out of it," Cano said.

His next door neighbor ran a hose over while Cano had his pump replaced and lowered deeper in the well. Cano returned the favor later that year when the neighbor's well dried up. Even now that their wells are working, the water quality is so poor that residents are provided 50 gallons (190 litres) of drinking water a month under a grant.

With less snow and temperatures warming due to climate change, another bad fire season is likely on the way, said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The state largely escaped fire devastation during the previous drought, but has suffered terribly since, after 100 million trees died and vegetation remained dry as a result of the drought. Since 2015, the state has experienced the largest, most destructive and deadliest fires in recorded state history;

Lund found that the drought caused about $10 billion in damages statewide, without direct loss of life. But the wildfires after caused a record of over $55 billion in direct property losses and 175 direct deaths, with possibly many other deaths and economic impacts due to weeks of widespread air pollution from smoke.

"The interesting thing about these other drought impacts is they happened after the drought ended," Lund said.