Residents of California's inland cities, long considered cheaper alternatives to the state's expensive coastal metros, are beginning to feel the effects of the state's housing affordability crisis.

Typical rent prices have shot up by as much as 40% in places like Bakersfield, Fresno, Visalia and Riverside in just three years, according to data from economists at the real estate listings company Zillow.

While rent in these cities remains considerably lower than the Bay Area or Los Angeles, they've seen the largest increases in rent across the entire state, putting sudden pressure on lower-income residents who rely on the lower costs of living of these areas.

Get top local stories in Southern California delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC LA's News Headlines newsletter.

In both Bakersfield and Los Angeles, average rent rose by a little over $500 since the start of the pandemic. However, because Bakersfield rents were vastly cheaper to begin with, that $500 increase has a much harder impact.

The average income in Kern County is around $25,000, according to the latest US Census data, while the average LA County resident makes about $38,000.

What's behind the rent hikes?

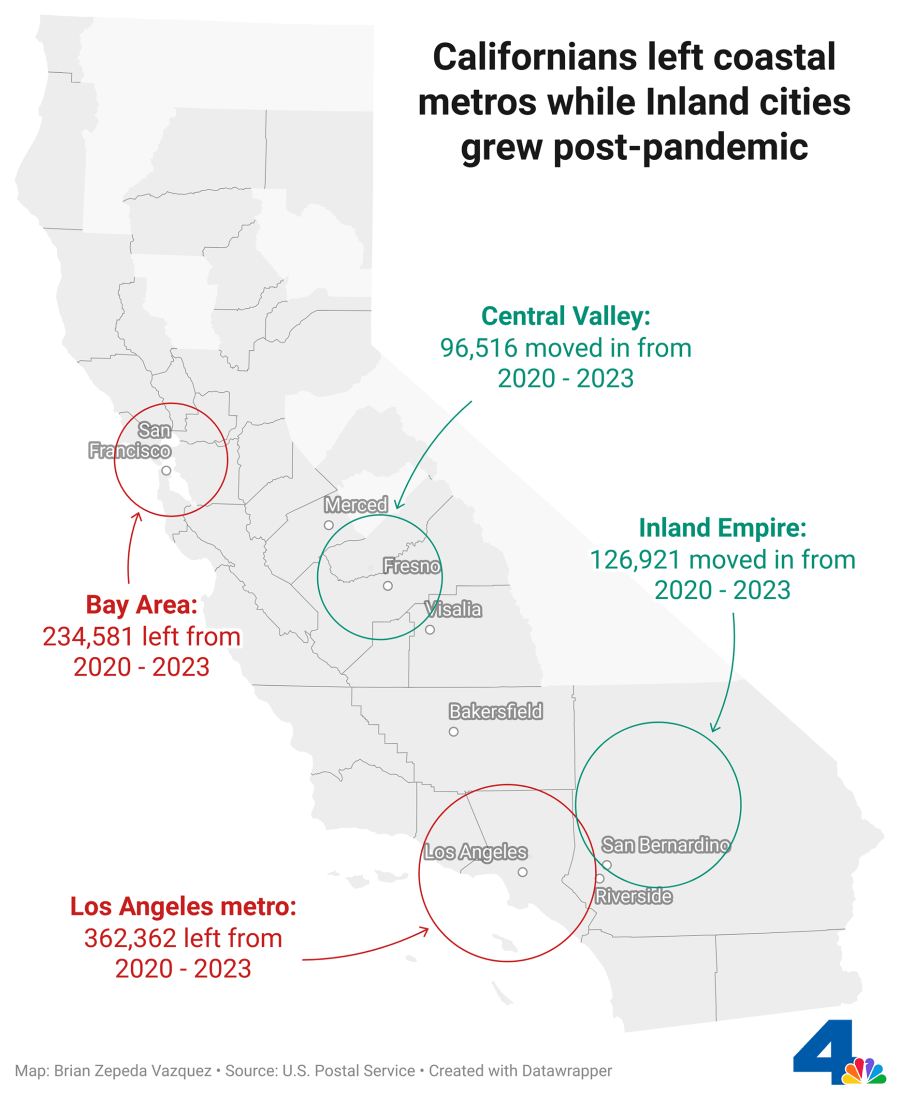

The sudden explosion in inland rent prices can be traced back to the COVID-19 pandemic and, more generally, California's already-existing housing crisis that has long pushed residents to more affordable cities inland and outside of the state.

The state's densely populated coastal areas saw a large loss of educated white-collar workers. Many left the state entirely, while others migrated further inland.

Nicole Bachaud, a senior economist on Zillow's research team, explained that places like Riverside or Bakersfield "provide opportunities for homeownership, especially in the world of remote work."

As millennials seek out homeownership, they're confronted with a market that is increasingly inaccessible. According to other data from Zillow, the typical mortgage payment in the Los Angeles area represents around 84% of someone's average monthly income. While that burden is down 10% from last year, it still represents a significant barrier to homeownership.

As property owners sold off their rentals to migrating homebuyers, inland communities started to see a shortage of one-bedroom units, increasing competition among renters.

Bachaud notes that rent prices saw their largest increases around 2021 driven by "a lot more rental demand, especially in places that had previously been more affordable."

While these historically affordable areas have provided accessible homebuying opportunities for newcomers, the large influx of people searching for housing has created financial strains for lower-income residents.

Shanti Singh, communications and legislative director for the Tenants Together coalition, described the situation as a "perfect storm," creating a "chain of displacement."

"People fleeing evictions and unaffordable rent hikes and housing in LA go further out, and then people from Bakersfield gets displaced," she said.

Singh explains that in places like the Central Valley, "historically, there has not been as many city-level tenant protections, if any," putting pressure on renters which only grew during the pandemic.

"If you were already struggling to pay your rent before COVID, and then you have losses of income caused by the pandemic and, on top of that, your landlord is responding to inflation by hiking your rent, that is a homelessness and displacement time bomb," Singh said.

Solving California's housing crisis

While the root of this widespread crisis is a shortage of affordable housing supply, tenants' rights organizations and activists have pushed for measures to address the immediate strain of rent hikes confronting tenants.

Singh described a wave of tenants' unions organizing in areas like the Central Valley within the last year. In June, activists campaigned for a rent control program in Fresno, which ultimately was unsuccessful.

Echoing a similar belief as Fresno city officials, Chapman University professor Joel Kotkin said, "the problem with rent control is that it solves the issue in the short-term, but it makes it very unappealing for developers to build new housing."

Still, Singh emphasized another perspective, saying that rent control is a "long-term formula for stability."

"There are positive outcomes that come out of keeping tenants stable in their communities," she said. "It's not the entire solution, of course, we just need to build more affordable housing."

A report by the California Department of Housing and Community Development published in 2000 estimated the state would need to build 220,000 additional units each year for 20 years to satisfy the state's then-growing population.

Still, more than two decades later, California has not caught up to that goal. Last year, which saw the highest number of units produced since 2008, the total count of housing built was still about 100,000 units short of meeting that number.

That same year, the department announced that 2.5 million new homes would need to be built over the next eight years, amounting to 315,000 units a year, to meet needs across the state.

Cities such as Bakersfield, Visalia, and Fresno have responded by approving approximately 15% more housing units in 2021 and 2022 compared to the two years before the pandemic, according to data from the California Department of Housing and Community Development.

"We really need to focus on building more affordable housing that's able to be maintained through programs like subsidized government loans that are also going to be able to help builders create affordable homes to fill the need for renters," said Bachaud.

Kotkin, and other experts, propose additional measures, such as reforming regulations like the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, to allow the building of new communities outside of the dense urban metros.

"The state regulatory environment has made it very difficult to build affordable housing of any kind," he said.

Kotkin points to the success of places like Irvine and Ontario Ranch, communities developed with a focus on sustainability and targeted for remote workers, as an example of what he describes as "smart sprawl."

“I think there could be a very good future for the Inland Empire and the Central Valley. It’s really the kind of place where California can reinvent itself," said Kotkin.

"What we have to do is make sure that the housing prices and rent don’t go so high that people want to leave.”