With anti-immigrant rhetoric bubbling over in the leadup to this year's critical midterm elections, about 1 in 3 U.S. adults believes an effort is underway to replace U.S.-born Americans with immigrants for electoral gains.

About 3 in 10 also worry that more immigration is causing U.S.-born Americans to lose their economic, political and cultural influence, according to a poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Republicans are more likely than Democrats to fear a loss of influence because of immigration, 36% to 27%.

Those views mirror swelling anti-immigrant sentiment espoused on social media and cable TV, with conservative commentators like Tucker Carlson exploiting fears that new arrivals could undermine the native-born population.

In their most extreme manifestation, those increasingly public views in the U.S. and Europe tap into a decades-old conspiracy theory known as the “great replacement,” a false claim that native-born populations are being overrun by nonwhite immigrants who are eroding, and eventually will erase, their culture and values. The once-taboo term became the mantra of one losing conservative candidate in the recent French presidential election.

Get top local stories in Southern California delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC LA's News Headlines newsletter.

“I very much believe that the Democrats — from Joe Biden and Nancy Pelosi, all the way down — want to get the illegal immigrants in here and give them voting rights immediately,” said Sally Gansz, 80. Actually, only U.S. citizens can vote in state and federal elections, and attaining citizenship typically takes years.

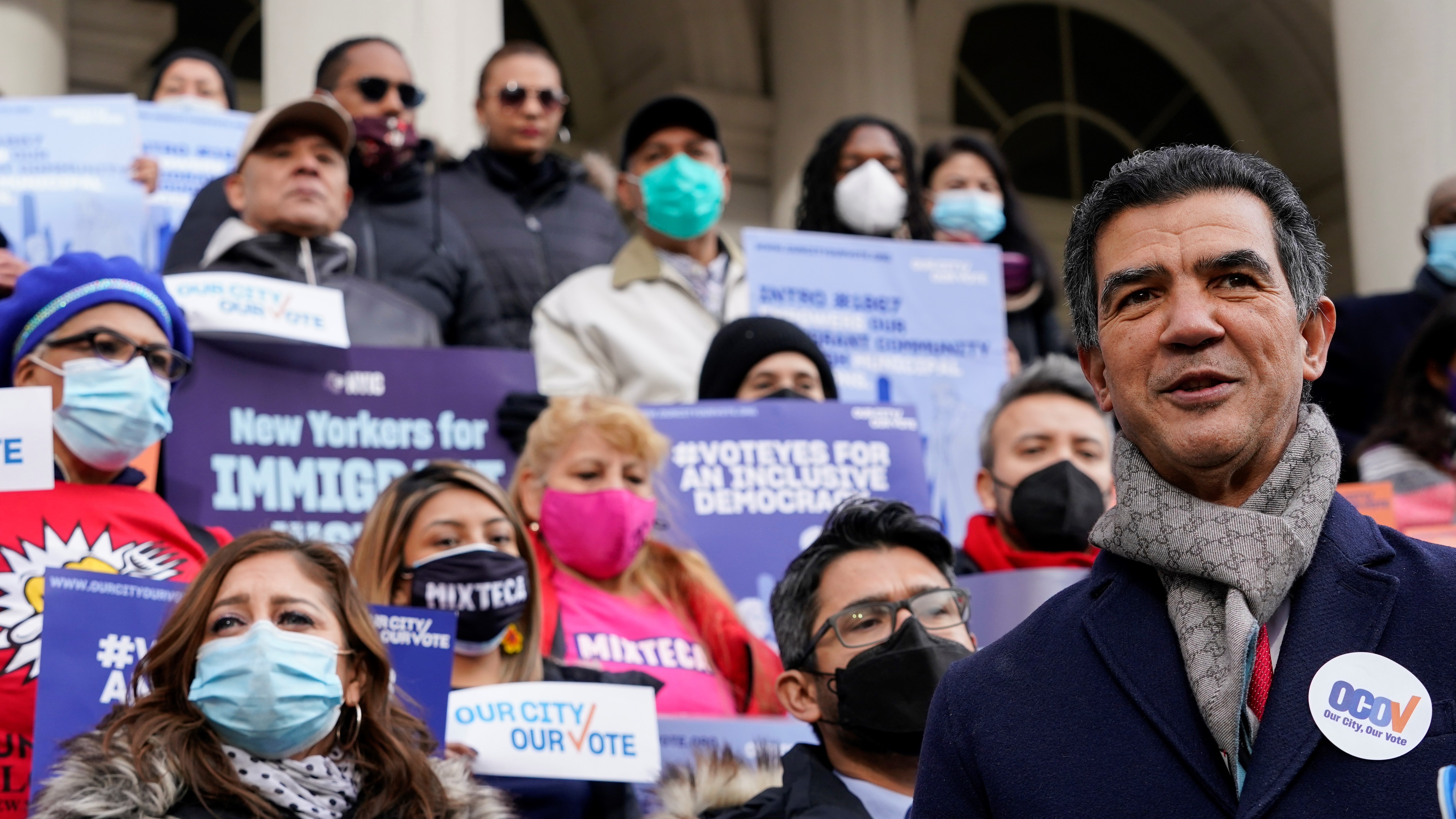

More than 800,000 noncitizens in New York City will have access to the ballot box for municipal elections as early as next year the city's mayor permitted legislation to become law in January.

More Elections Coverage

A white Republican, Gansz has lived her whole life in Trinidad, Colorado, where about half of the population of 8,300 identifies as Hispanic, most with roots going back centuries to the region’s Spanish settlers.

“Isn’t it obvious that I watch Fox?” quipped Gansz, who said she watches the conservative channel almost daily, including the top-rated Fox News Channel program “Tucker Carlson Tonight,” a major proponent of those ideas.

“Demographic change is the key to the Democratic Party’s political ambitions,” Carlson said on the show last year. “In order to win and maintain power, Democrats plan to change the population of the country.”

Those views aren't held by a majority of Americans — in fact, two-thirds feel the country’s diverse population makes the U.S. stronger, and far more favor than oppose a path to legal status for immigrants brought into the U.S. illegally as children. But the deep anxieties expressed by some Americans help explain how the issue energizes those opposed to immigration.

“I don't feel like immigration really affects me or that it undermines American values,” said Daniel Valdes, 43, a registered Democrat who works in finance for an aeronautical firm on Florida's Space Coast. “I’m pretty indifferent about it all.”

Valdes' maternal grandparents came to the U.S. from Mexico, and he said he has “tons” of relatives in the border city of El Paso, Texas. He has Puerto Rican roots on his father's side.

While Republicans worry more than Democrats about immigration, the most intense anxiety was among people with the greatest tendency for conspiratorial thinking. That's defined as those most likely to agree with a series of statements, like much of people's lives are "being controlled by plots hatched in secret places” and “big events like wars, recessions, and the outcomes of elections are controlled by small groups of people who are working in secret against the rest of us.”

In all, 17% in the poll believe both that native-born Americans are losing influence because of the growing population of immigrants and that a group of people in the country is trying to replace native-born Americans with immigrants who agree with their political views. That number rises to 42% among the quarter of Americans most likely to embrace other conspiracy theories.

Alex Hoxeng, 37, a white Republican from Midland, Texas, said he found those most extreme versions of the immigration conspiracies “a bit far-fetched” but does believe immigration could lessen the influence of U.S.-born Americans.

“I feel like if we are flooded with immigrants coming illegally, it can dilute our culture,” Hoxeng said.

Teresa Covarrubias, 62, rejects the idea that immigrants are undermining the values or culture of U.S.-born Americans or that they are being brought in to shore up the Democratic voter base. She is registered to vote but is not aligned with any party.

“Most of the immigrants I have seen have a good work ethic, they pay taxes and have a strong sense of family,” said Covarrubias, a second grade teacher in Los Angeles whose four grandparents came to the U.S. from Mexico. “They help our country.”

Republican leaders, including border governors Doug Ducey of Arizona and Greg Abbott of Texas — who is running for reelection this year — have increasingly decried what they call an “invasion,” with conservative politicians traveling to the U.S.-Mexico border to pose for photos alongside former President Donald Trump’s border wall.

Vulnerable Democratic senators up for election this year in Arizona, Georgia, New Hampshire and Nevada have joined many Republicans in calling on the Biden administration to wait on lifting the coronavirus-era public health rule known as Title 42 that denies migrants a chance to seek asylum. They fear it could draw more immigrants to the border than officials can handle.

U.S. authorities stopped migrants more than 221,000 times at the Mexican border in March, a 22-year high, creating a fraught political landscape for Democrats as the Biden administration prepares to lift Title 42 authority on May 23. The pandemic powers have been used to expel migrants more than 1.8 million times since it was invoked in March 2020 on the grounds of preventing the spread of COVID-19.

Newly arrived immigrants are barred from voting in federal elections because they aren’t citizens, and gaining citizenship is an arduous process that can take a decade or more — if they are successful. In most cases, they must first obtain permanent residency, then wait five more years before they can apply for citizenship.

Investigations have failed to turn up evidence of widespread voting by people who aren't eligible, including by non-citizens. For example, a Georgia audit of its voter rolls completed this year found fewer than 2,000 instances of non-citizens attempting to register and vote over the last 25 years, none of which succeeded.

Blake Masters, a candidate for Senate in Arizona, is among the Republicans running for office this year who have played into anxieties about a changing population.

“What the left really wants to do is change the demographics of this country," he said in a video recorded in October. “They want to do that so they can consolidate power so they can never lose another election.”

The AP-NORC poll of 4,173 adults was conducted Dec. 1-23, 2021, using a combined sample of interviews from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population, and interviews from opt-in online panels. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is plus or minus 1.96 percentage points. The AmeriSpeak panel is recruited randomly using address-based sampling methods, and respondents later were interviewed online or by phone.